Four decades after allegations initially surfaced of a secret mission by Ronald Reagan’s 1980 presidential election campaign to derail President Jimmy Carter’s re-election bid by sabotaging his efforts to free 52 American hostages being held in Iran, the New York Times is finally giving the story the attention it deserves by publishing a front-page story on Saturday that features fresh claims of a Republican ploy.

The allegations are startling and provide one more puzzle piece to solving the mystery, going a long way toward removing any lingering doubt that the plot did happen – suggesting, indeed, that the Reagan era may have been ushered in by an act of treason that extended the hostages’ harrowing ordeal by several months.

“It has been more than four decades,” the Times story begins, “but Ben Barnes said he remembers it vividly. His longtime political mentor invited him on a mission to the Middle East. What Mr. Barnes said he did not realize until later was the real purpose of the mission: to sabotage the re-election campaign of the president of the United States.”

The mentor that Barnes was accompanying was John B. Connally Jr., a former Democrat who ran in the Republican primaries in 1980 and then, after losing the nomination, threw in his lot with the campaign of Ronald Reagan. Connally was committed to help Reagan beat Carter and hoped to win a cabinet post in a new administration.

“What happened next Mr. Barnes has largely kept secret for nearly 43 years,” according to the Times. “Mr. Connally, he said, took him to one Middle Eastern capital after another that summer, meeting with a host of regional leaders to deliver a blunt message to be passed to Iran: Don’t release the hostages before the election. Mr. Reagan will win and give you a better deal.”

In the lengthy and well-researched article, Times reporter Peter Baker notes that records at the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library and Museum in Austin, Texas confirm part of Barnes’s story, namely an itinerary found in Connally’s files that showed that in the summer of 1980 he did, in fact, travel to Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Israel. The itinerary showed he departed Houston on July 18, 1980, returning on Aug. 11, and lists Barnes as an accompanying person.

The allegations also mesh with previous reporting done on the subject by my late father, Robert Parry. As Baker notes, while Barnes’s claims of a Connally-led trip are new, they are bolstered by documents uncovered by my dad, and fit into a pattern of other alleged trips in the summer and fall of 1980 to prevent Carter from reaching a deal to free the hostages.

Earlier attempts to debunk the October Surprise relied on a dubious alibi for Reagan’s campaign director William Casey, who was long suspected of participating in a key meeting with Iranians in Madrid in late July 1980. Although a 1992 congressional investigation led by House Democrat Lee Hamilton dismissed this allegation as unfounded, a White House memo from 1991 reported the existence of “a cable from the Madrid [U.S.] embassy indicating that Bill Casey was in town, for purposes unknown.”

That memo, produced by one of President George H.W. Bush’s lawyers, “was not turned over to Mr. Hamilton’s task force and was discovered two decades later by Robert Parry, a journalist who helped produce a ‘Frontline’ documentary on the October surprise,” Baker reports in the Times piece.

Barnes’s claims of a whirlwind trip to the Middle East also fit in well with what is known about Connally. As my father reported more than a quarter-century ago, Connally was among the most gung-ho of Reagan’s backers, and just before the election in 1980, he had troubling news for the campaign.

X-Files

While on the campaign trail, my dad wrote, Republican vice presidential nominee George H.W. Bush got a call from Connally, telling him that “the oil-rich Middle East was buzzing with rumors that President Carter had achieved his long-elusive goal of a pre-election release of 52 American hostages held in Iran. If true, Ronald Reagan’s election was in trouble.”

Bush then called Richard Allen, a senior Reagan foreign policy adviser who was keeping track of Carter’s hostage progress, tasking him to find out what he could about Connally’s tip. My dad found Allen’s notes in early 1993 in an obscure Capitol Hill storage room. These were the “X-files” from the 1992 congressional investigation – documents that didn’t support the official narrative and were thus omitted from the final report.

“Geo Bush,” Allen’s notes began, “JBC [Connally] – already made deal. Israelis delivered last wk spare pts. via Amsterdam. Hostages out this wk. Moderate Arabs upset. French have given spares to Iraq and know of JC [Carter] deal w/Iran. JBC [Connally] unsure what we should do. RVA [Allen] to act if true or not.”

It was after this that Casey and Bush allegedly shuttled to Paris to meet face-to-face with Iranian mullahs on Oct. 19, 1980, in order to block any last-minute deal with Carter.

As my father reported, “Four French intelligence officials, including France’s spy chief Alexandre deMarenches in statements to his biographer, placed Casey at the Paris meeting. But two other witnesses, a pilot named Heinrich Rupp and Israeli intelligence official Ari Ben-Menashe, also claimed to have seen Bush in Paris that day. Ben-Menashe testified that Casey and Bush were accompanied by active-duty CIA officers.”

The new reporting by the New York Times mentions this meeting in passing, noting that “Casey was alleged to have met with representatives of Iran in July and August 1980 in Madrid leading to a deal supposedly finalized in Paris in October in which a future Reagan administration would ship arms to Tehran through Israel in exchange for the hostages being held until after the election.”

In the next paragraph, however, Baker effectively dismisses the claims by pointing out that congressional investigations debunked them. “The bipartisan House task force, led by a Democrat, Representative Lee H. Hamilton of Indiana, and controlled by Democrats 8 to 5, concluded in a consensus 968-page report that Mr. Casey was not in Madrid at the time and that stories of covert dealings were not backed by credible testimony, documents or intelligence reports,” Baker reports.

The credulity with which the Times treats the Hamilton-led investigation is woefully undeserved. As my father reported in the 1990s, the congressional task force that looked into the October Surprise allegations suppressed credible evidence and relied on alibis for Casey and other key figures that were frankly absurd.

One of these alibis was the fact that a Republican operative wrote Casey’s phone number down on a particular day, which satisfied the congressional investigators that Casey must have been at home – even though no phone call was apparently placed.

The faith that Baker places in this investigation, however, is par for the course for the New York Times. On Jan. 24, 1993, the paper published an op-ed by Hamilton, entitled “Case Closed.” It cited Casey’s alibis as key reasons why his task force’s findings “should put the controversy to rest once and for all.” With this high-profile article, the Times contributed to a significant degree in making the story toxic for any fair-minded journalist who dared to continue following the leads.

While the newfound attention on the case by the Times is certainly welcome and timely, especially considering President Carter’s imminent passing, it is a shame that the reporting perpetuates some of the longstanding flaws in the media’s handling of this story.

Not only is it overly credulous when it comes to the “congressional investigations [that] debunked previous theories of what happened,” but the Times also goes out of its way to denigrate previous sources “who fueled previous iterations of the October surprise theory,” claiming that they tended to be “shady foreign arms dealer[s] with questionable credibility.”

Although some sources for the October Surprise story were in fact arms dealers (which would make sense considering that a central component of the story was the illegal transfer of weapons to the Iranian regime), there are quite a few other sources that corroborate their claims. Among the individuals that have gone on record about the deal were Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat and Abolhassan Bani-Sadr, Iran’s first post-revolution president.

In his 1991 memoir, My Turn to Speak, Bani-Sadr wrote that “in late October 1980, everyone was openly discussing the agreement with the Americans on the Reagan team.” He claimed that “Carter was no longer in control of U.S. foreign policy and had yielded the real power to those who … had negotiated with the mullahs on the hostage affair.”

The Russian Report

Classified documents uncovered by my father, which were never meant to see the light of day, also bolstered the claims. A 1992 secret report from the Russian government, for instance, asserted that “William Casey, in 1980, met three times with representatives of the Iranian leadership … in Madrid and Paris.”

“In Madrid and Paris,” the Russians explained, “the representatives of Ronald Reagan and the Iranian leadership discussed the question of possibly delaying the release of 52 hostages from the staff of the U.S. Embassy in Teheran.”

Casey’s alibi of supposedly being at the Bohemian Grove in California when a key meeting was taking place with Iranians in Madrid was also shattered when my father discovered a group photo from the Bohemian Grove in which Casey was conspicuously absent.

But no matter how much evidence was produced over the years that poked holes in the official story, the establishment media declined to re-examine the case or treat it seriously.

In fact, it was largely due to the media’s disinterest in covering this story honestly that my father decided to launch his independent media project in 1995, including the Consortium News website, a newsletter and magazine, as well as a small book publishing house. The first book published was The October Surprise X-Files, which made public much of the evidence establishing that a conspiracy did in fact take place.

The Times’ newfound interest in the story is welcome, but at the same time, it shouldn’t be forgotten how the media failed the American people when it mattered most.

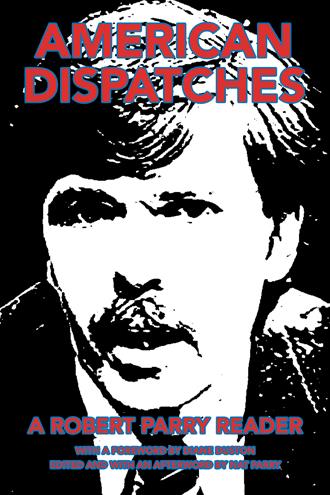

Nat Parry is the editor of the recently published collection of Robert Parry’s journalism spanning five decades, American Dispatches: A Robert Parry Reader, which contains much of the original reporting on the October Surprise story. He is also the co-author of Neck Deep: The Disastrous Presidency of George W. Bush and author of How Christmas Became Christmas: The Pagan and Christian Origins of the Beloved Holiday.